How Bank of Russia and Russian Central Banking is coping with war and other political expediencies

War and Peace

War and Peace, Tolstoy’s enduring masterpiece, starts with a party scene. Set in the St Petersburg of 1805, the main characters are introduced here. Most of us would have read the ‘novel’ (Tolstoy did not call it one) in English. Lost in translation is the fact that almost the entire conversation, page after page, is in French. It was the preferred language of the Russian aristocracy. For Tolstoy, it was a literary device. He was making fun of the nobles of the day who spoke French to flaunt their exclusivity. He wanted to show how disconnected they were from core Russian values and the world around.

Tolstoy started writing his historical novel in the Tsarist Russia of 1863. By then, Russia already had a central bank in its State Bank of the Russian Empire for three years. France had already had a central bank in its Banque de France, five years before the period that Tolstoy covered.

Money, debt, and financial misdemeanour abound in the great Russian classics of the 19th century. Unpaid debts leading to a murder in Dostoyevsky’s Crime and Punishment. Deceit in Pushkin’s Dubrovsky. Get rich quick schemes in Gogol’s Dead Souls.

History

Early years

Starting in 1860, the Bank of Russia has had a chequered history. In 1865, as part of Emancipation Reform, the State Bank tracked payments made by peasants for plots bought from landlords. In 1872, it started issuing loans to small lenders, whose borrowers were peasants and artisans. More than a decade later, in 1884, it started issuing loans to landlords. The new State Bank charter of 1894 focused on industrial loans for developing small- and medium-sized industrial production and trade.

After the 1905 revolution, the Bank created a Moscow banking consortium to help Russian trade and industrial firms. When war broke out in 1914, the State Bank stopped exchanging notes for gold.

October revolution

On 25 October 1917 (as per the Julian calendar, 7 November as per the Gregorian calendar), the Bolsheviks occupied the State Bank premises in Petrograd. Its name was changed in 1914 from St Petersburg which sounded too German. In December, banking was nationalised, and gold coin and bullion confiscated and transferred to a national gold fund. Apprehending a foreign invasion, Lenin shifted the capital to inland Moscow in the following March.

In 1918, the People’s Bank of the Russian Soviet Republic was established. It was liquidated in 1920, when the State Bank of the RSFSR was established.

In 1923, the State Bank of the RSFSR was reorganised into the State Bank of the USSR or the Gosbank. This was what I studied as an undergraduate in the late 1970s, in my optional paper on central banking and banking systems. The central bank of Russia, then in the Soviet Union, or the USSR, was known simply as Gosbank. This was a short form for Gosudarstvennyi Bank SSSR which in turn meant the State Bank of the USSR.

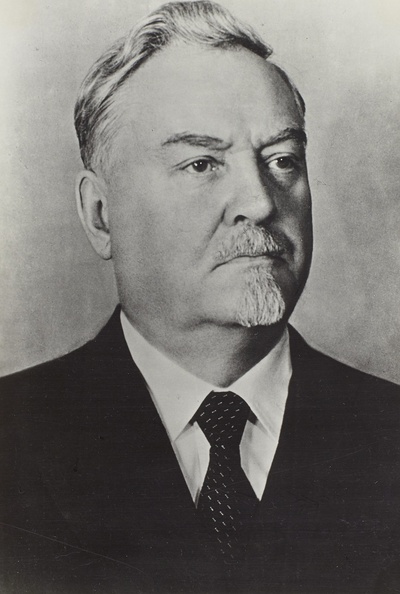

Among the Gosbank’s Governors, for three terms, was Nikolai Bulganin whose name is immortalised by the beard that he sported. Bulganin later became the Premier from 1955 to 1958 before Nikita Khrushchev succeeded him. That Bulganin was earlier a Governor of the Gosbank is a new discovery for me. So, I stand corrected from what I wrote earlier that Josef Tosovsky of Czechoslovakia was the first central bank Governor later heading a government, much before Manmohan Singh in India and Mario Draghi in Italy.

The 70s and 80s

The Russian banking system in the late 70s was fairly simple and straightforward. In fact, that was the case till around 1991. Gosbank was the only real bank. It combined central banking and commercial banking functions. In addition, there were five specialized banks (or spetsbanki) serving different sectors of the Soviet economy. The bank attached to their names was a misnomer. These were the Industrial Bank (Prombank), Agricultural Bank (Sel’khoz Bank), Bank for the Financing of Capital Construction in Trade and in the Cooperative Sector (Torgbank) and the Central Bank for the Financing of Communal and Dwelling Construction (Tsekombank) and the community banks affiliated to it. Established later was the Vneshekonombank USSR or the Bank for Foreign Economic Affairs. And then there were the far-flung savings banks that came under the Gosbank. These are now part of the government-owned Sberbank, the largest Russian bank.

(Aside: Whoever valued my final examination paper did not sufficiently reward me for remembering these names. Maybe she thought I was bluffing my way)

In the 1970s and 1980s, the two decades before the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Bank of Russia was the largest central bank in the world. It had between 60,000 and 80,000 employees working across 80 regional offices and 500 cash settlement centres. Most of the employees were in regional offices which mainly handled banking supervision and cash operations. Apart from a network of 14 banking schools, it had one central personnel training centre, one interregional training centre, and three regional training centres for the branch staff.

Perestroika

A major shakeup happened only with the perestroika (restructuring) of Mikhail Gorbachev. Some of the spinoffs, like Vneshtorgbank (VTB) or International Trade Bank and Sberbank (Savings Bank) survive to this day with a nominal presence in New Delhi. (Sberbank started operations in New Delhi when I was heading banking supervision there, the second Russian bank in India following JSC-VTB.)

For a detailed timeline of the history of central banking in Russia, see here.

Russian banking of 1990s

After Gorbachev introduced perestroika, where he looked at Hungary and China as models, the ‘animal spirits’ were let loose. Years of controlled decision making and state-watch must have reined in the urge to let go. This was not without adverse consequences. According to Johnson (2018), Russians described the result in one word, bespredel: without limits. As she describes:

“Fortunes were made and lost, corruption and criminality ran rife, uncertainty reigned, and indeed, everything and anything seemed possible. These years saw the rise of the so-called oligarchs, the band of commercial bankers who loomed so large over the political system that prominent academics and policy makers spoke of Russia as a captured state. Both wealth and political power became concentrated quickly and jokes about the ‘New Russians’ of Moscow with more money than taste, empathy or ethics proliferated.”

Johnson, J. The Bank of Russia: from central planning to inflation targeting

In the middle of all this, the Bank of Russia seemed to beat a different path. As Johnson further elaborated:

“Yet amid the thievery, the venality, the political instability, and the Soviet-era norms and practices that made Russia nearly the last place one might expect to find Western style institution building, the Bank of Russia seemed to be changing faster than it had any right to under the circumstances. Already by the end of that tumultuous decade, the massive bureaucratic heir to the Soviet Gosbank had developed a reputation as one of the least corrupt and most professional Russian government institutions.”

Johnson, J. The Bank of Russia: from central planning to inflation targeting

Reaffirming this point of view, she quoted an international adviser as saying that “I trust the Central Bank of Russia much more than any other Russian institution, although this is because everything is relative.”

Contrasting central bankers

Nevertheless, as explained by the relativity, the Bank of Russia had in its early years a Governor in Viktor Gerashchenko for two terms. This was in addition to his term in the erstwhile Gosbank. In 1993, Jeffrey Sachs called him the world’s worst central banker.

In contrast was Andrey Kozlov (1965-2006) who was brought to the Board while only 30 years old. He became the first Deputy Chairman two years later. He held this post from 1997 to 1999 and again from 2002 to 2006. Kozlov represented the new generation of Russian central bankers. But, he never became Governor and as we shall see below, met with a tragic end.

Early years of liberalisation

The early years following perestroika were chaotic. In this period, both Gosbank and Bank of Russia coexisted following a hurriedly prepared and messed up piece of legislation. Johnson describes the result thus:

“This political battle for sovereignty provided few incentives (and indeed, some significant disincentives) for the central bankers to increase their technical capabilities or to stop funneling cheap credits to state enterprises. Instead, Gosbank and the Bank of Russia competed to offer easier registration and lighter regulation to the rapidly proliferating commercial banks. As a result, when the Soviet Union collapsed and the Bank of Russia swallowed Gosbank in late 1991, Russia had a relatively independent central bank but one whose institutional framework, internal culture, and technical capabilities had otherwise changed little.”

Johnson, J. The Bank of Russia: from central planning to inflation targeting

For Gerashchenko and Gosbank, in the initial years of decentralisation, managing the spetsbanki and maintaining monetary sovereignty over 15 Soviet republics was increasingly difficult. The initial law created a US Federal Reserve style system of regional central banks with the Gosbank at the centre. It also made Gosbank independent of the executive but accountable to the USSR Supreme Soviet. In another radical change, and for the first time in Soviet history, limits were put in place for Gosbank funding of the Ministry of Finance.

Russia and the CIS

In the reform years, the IMF and many central banks played a role in preparing Russia and the Confederation of Independent States (CIS) for introducing market-based economies. These central banks included the Bank of England, Bundesbank, and Bank of France providing training and technical assistance. In the end, Russian central bankers earned a reputation for taking its inflation fighting and banking supervision seriously and making Bank of Russia more professional.

Monetary policy

The IMF considers Bank of Russia take inflation fighting seriously, especially during 1992 to 1995, as one of its major successes. At the same time, allowing the ruble zone to continue beyond its shelf life was a major failure. Finally, Bank of Russia killed it on its own by issuing new ruble notes while invalidating the earlier ones. As Johnson observed, an earlier breakup would have made the process better coordinated and less costly.

Following the Black Tuesday of 1994 when ruble fell by 30 per cent, more reforms were set in. Gerashchenko resigned owning responsibility. Under his protégée, Paramonova, who succeeded him as acting director, and the new governor, Sergei Dubinin, “its staff began to understand open market operations, grasped the role of monetary policy committees, and learned to read Bloomberg data screens.” Kozlov remembered this time as when IMF pushed the staff to draft their own policy but using Western standards and methods (Johnson, 2018).

The GKOs

Among the reforms were new short-term treasury instruments known as GKOs (short for gosudarstvennye kratkosrochnye obligatsii). For this, Kozlov’s team visited New York and Chicago to learn how to create the technical infrastructure for a securities market. A ‘ruble corridor’ introduced in July 1995 promised to keep the ruble-dollar exchange rate within limits. But, opening the GKO market to foreigners in 1996 resulted in a rush of speculative capital. Scandal struck in 1997 when USAID admitted to its consultants from Harvard Institute for International Development engaged in insider trading.

Around the same time, the Asian crisis was unfolding in five East Asian countries. This and falling crude oil prices destroyed the ruble corridor and the GKO pyramid. The stock market also tumbled. The forex outgo in November 1997 from the GKO market was about $5 billion The attempts to restore order and confidence went beyond the start of the new millennium.

Subsequently, the dollar depreciation before the global financial crisis complicated matters for the Bank of Russia. By then, Bank of Russia announced allowing greater exchange rate volatility as a move towards inflation targeting.

Banking supervision

At the dawn of the post-Soviet era, there were 1360 commercial ‘banks.’ With further breakup of the system, this soon grew to around 2000. As Johnson highlights, these “banks made their money primarily through political patronage, connected lending, currency trading, and other speculative and downright illicit activities.” The Yeltsin government kept squeezing banks for funds so much so that the Sberbank came to be nicknamed the Ministry of Cash.

This was also a period when regulations were sought to be brought on par with global standard. The criticism was that the “Bank of Russia ‘took its regulations from international textbooks, but without any real understanding’, and pointed out that its directives included text translated directly from the Basel accords.”

But, global pressure had its beneficial impact in the Bank of Russia finally letting go of commercial bank ownership. One exception was Sberbank which remained with the Bank for fear of privatisation or restructuring destabilising the system.

The IMF’s Financial System Stability Assessment (FSSA) of Russia in 2002–03 provided an opportunity. Kozlov found support in its report for his plans for deposit insurance, introducing the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS), tightening capital requirements, introducing risk-based supervision, and strengthening prompt corrective action.

The progress was slow and uneven even under Kozlov. The bankers and auditors that Johnson spoke to criticised the introduction of IFRS being botched. What came in for particular criticism was ‘dedicated supervision’, where a dedicated supervisor dealt with one bank. Given the cultural underpinnings then at work, this arrangement only paved the way for corruption.

The backlash from banks was more aggressive and pointed towards Kozlov himself. Deposit insurance was to consolidate banks, keeping the stronger ones and removing the others. However, the pressures were such that the Bank had to finally admit 75% of the banks.

Sodbiznesbank

The licence of Sodbiznesbank was revoked for being connected to unlawful activities. The bank’s response was severe. It barred the central bank officials from its offices, arranged demonstrations, and ran a media campaign that many other banks would face a similar action. The last one resulted in runs on several banks. Even though the Bank of Russia and the government stood by Kozlov, according to Johnson, ‘public reputation took a beating.’

A votary of being sensitive to how Russian banking is viewed by the global financial community, Kozlov went ahead with a second upgraded Strategy for the Development of the Russian Banking Sector. Over four years, it aimed at liquidating banks with capital less than five million euros and pursue introduction of Basel II norms.

Unfortunately, Kozlov paid for his reform push with his life. In September 2006, contract killers shot dead Kozlov outside a Moscow sports stadium. The day before, he had told a banking conference in Sochi that “Those who have been found out laundering criminal money should probably be barred from staying in the banking profession for life. Such people disgrace the banking system.”

The killing was later revealed to have been ordered by Alexei Frenkel, who owned Sodbiznesbank and three others whose licences were withdrawn. The murder shocked the Russian and global financial community. Thereafter, reforms took a backseat. It got a fresh life only after the Global Financial Crisis.

Global Financial Crisis

With the global financial crisis in late 2008, the Russian economy was faced with increasingly adverse terms of trade, capital flight and a swift fall in the price of crude oil, its major export. The consequent sharp and steady fall in the ruble led to a flight to relatively stronger currencies, namely, US dollar and the Euro. Among other developments, rapid decline in share prices tripped trading in stock markets, banks and companies with foreign-currency liabilities were affected, and sources of credit disappeared. Ultimately, Russian GDP fell by around 8 percent.

Putin is back

Vladimir Putin returned to the Russian presidency in 2012. With his government advocating a new economic order, at home, regionally, and globally, the central bankers stuck to their defence of independence and price stability objectives while at the same time adjusting to the political demands. The monetary policy head, Ksenia Yudaeva, defended a four per cent inflation target while quoting Bundesbank’s Otmar Emminger: ‘If you flirt with inflation, you’ll end up marrying her.’

The new government also wanted to promote the ruble as a global currency. This required confidence in the currency and support to the central bank in its independence and inflation objectives. Even though inflation targeting starting during the tenure of the previous President Medvedev, it got more support after Putin came back as President in 2012. Putin appointed Elvira Nabiullina, his economic adviser, as Governor of Bank of Russia, in June 2013. It gave rise to fears that she would compromise the Bank’s independence and price stability mandate. This period also saw the expansion of the Bank’s mandate to include economic growth and significant regulatory and supervisory powers.

The Elvira Era

Elvira Nabiullina has been Governor of the Bank of Russia since 2013. Born in 1963 to a chauffeur father and a factory manager mother, she came up the hard way. Her grim and business-like demeanour and hair style in most official pictures reminds me of the lady in American Gothic, the iconic 1930 painting by Grant Wood. Her father, menacingly next to her with a pitchfork, could be a distant uncle of Putin.

Governor Nabiullina is not new to crises. Dealing with sanctions following the Russian annexation of Crimea in 2014 and the Covid challenge from 2020 have preceded the current set of sanctions following the war with Ukraine. The 2014 disruption was more severe than the Global Financial Crisis.

But, this time the challenges are more. Putin has backed her with a third term starting in June this year. She could end up becoming the longest serving lady Governor of a central bank.

The Ukrainian challenge

The Crimean annexation of 2014 and the western sanctions that followed faced Russia and its central bank with challenges of a magnitude not seen since the cold war era. But, it also provided opportunities and an ability to deal with future crises. When Visa and MasterCard suspended their service, the Bank of Russia introduced the National Card Payment System in June 2014. Fresh legislation mandated that Visa and MasterCard make huge deposits with the Bank of Russia to resume operations. When global rating agencies downgraded Russian assets to junk status, Russia started one in 2015 under the Bank of Russia. The new arrangements enhanced national autonomy, security and independence.

During the period following the sanctions, Governor Nabiullina reiterated the Bank’s commitment to independence, inflation targeting and structural reforms. The Bank spent $125 billion in 2014 to smoothen the fall of the ruble while reiterating commitment to inflation targeting. It also raised its key rates to 17% in December 2014. inflation-targeting goal. Notwithstanding its best efforts and the odds against which it was fighting the reactions were unkind. As Johnson concluded:

“Despite continuing support from Putin and the international central banking community, significant swaths of the Russian elite, press and public blamed the Bank of Russia for choking the economy with its high interest rates and with destabilizing the ruble, decrying it as a ‘foreign agent’.”

Challenges

War and Peace was written in the context of French invasion of Russia. The present context is the Russian invasion of its earlier state, Ukraine. The impact of a Russian default can be felt beyond borders. Take the case of ‘Long Term Capital Management’, run by Nobel laureates, that folded up in 1998, if one needed a reminder.

An IMF statement following the sanction stated as follows:

“The sanctions announced against the Central Bank of the Russian Federation will severely restrict its access to international reserves to support its currency and financial system. International sanctions on Russia’s banking system and the exclusion of a number of banks from SWIFT have significantly disrupted Russia’s ability to receive payments for exports, pay for imports and engage in cross-border financial transactions. While it is too early to foresee the full impact of these sanctions, we have already seen a sharp mark-down in asset prices as well as the ruble exchange rate.”

Measures announced on 18 March

With the western sanctions leading to the ruble tumbling by 29%, the Board of Bank of Russia met on 18 March 2022. In a short and crisp statement following the meeting, Governor Nabiullina assured that the Bank of Russia will implement all necessary measures to maintain financial and price stability, support the Russian financial sector, and protect the welfare of citizens and the economy in general. She added that the domestic financial infrastructure will continue to operate smoothly. The financial messaging system (FMS) can replace SWIFT inside Russia and allow connection of foreign participants. The National Payment Card System processes the entire traffic on payment cards inside Russia. International payment systems cards issued by the sanctioned banks will continue to operate inside Russia as normal.

Specific steps

Governor Nabiullina further specified steps to take care of the fallout from the current crisis. Here are a few excerpts/highlights:

Sanctions raised the ruble exchange rate and limited opportunities for Russia to use its gold and foreign currency reserves. The dynamics of the exchange rate is an additional pro-inflationary factor that affects the current product prices and causes a drastic rise in devaluation expectations and inflation expectations.

The Bank of Russia will employ a wide range of tools to maintain financial stability.

The Bank raised its key rate to 20%. “In order to support the attractiveness of deposits and protect households’ savings against depreciation, we need to raise interest rates to the levels that would compensate for higher inflation risks for people.”

Other measures

Given the abnormal situation that Russia’s financial system and economy are facing, Nabiullina assured that the “Bank of Russia will use any necessary tools very flexibly.” This was an echo of Mario Draghi’s famous “whatever it takes.”

To prop up banking sector liquidity, the Bank of Russia is “continuously providing cash and non-cash rubles to banks.” But, the high demand for cash has led to a structural liquidity deficit in the banking sector. The Governor reassured that “Banks have sufficient collateral to increase the amount of liquidity raised from the Bank of Russia.”

In the foreign exchange market, the Bank of Russia intervened to the extent of one billion US dollars on 16th and to a smaller amount on 17th. Due to restrictions on using gold and forex reserves in dollars and euros, the Bank made no interventions on the 18th.

The Government made it obligatory for exporting ‘enterprises’ to sell 80% of their export revenues to ensure even supply of foreign currency in the domestic forex market. At the same time, the Bank of Russia has also limited the withdrawal of capital by non-residents including restrictions on securities sales.

Regulatory relaxations

This includes allowing banks not to revalue investment in securities and foreign currency assets and liabilities for calculating capital adequacy ratios so that banks can “gradually adjust to the new environment.”

The Bank will not force banks sanctioned by foreign states to comply with open currency position limits.

Banks need not increase their provisions during the year.

As part of countercyclical macroprudential policy, the Bank released accumulated buffers for all loan types, including foreign currency loans to companies and household loans. These measures are equivalent to an increase in banks’ capital by 900 billion rubles.

The Bank of Russia recommended that banks restructure retail and corporate loans without imposing penalties and fines or decreasing their financial standing and debt servicing quality.

Banks should not change conditions on current loans issued at fixed interest rates. If a borrower is facing hardships with a loan at a floating rate and the bank is ready to restructure such a loan, the Bank of Russia would grant regulatory easing for provisions.

Suspended limit on total cost of a consumer loan. Will adjust macroprudential buffers for unsecured and mortgage loans and will only leave the buffers for the riskiest loans, that is, loans with the highest total cost of credit, high payment-to-income ratios and, in mortgage, high loan-to-value ratios.

All banks are fulfilling and will continue to fulfill all obligations to their clients. All funds in clients’ accounts are preserved, and all transactions are available to clients.

Regulatory easing to insurers and professional securities market participants.

Reading Governor Nabiullina

Different central bankers over the years have carved out their own ways of communicating to the media and the public. Examples abound from the 19th century to Greenspan in the 1990s. Nabiullina has etched her own mark with her covert messaging. Speaking in Russian, and often addressing those who know little of it, she would have had to resort to visual props. Sometimes, it is the dress. On other occasions, it is her brooches just as Madeleine Albright used pins to express her moods. (I saw news of Albright passing away as I was writing this).

The brooches sometimes take the shape of a house, a hawk, a pigeon (the Russian word also meaning a dove), blue wave, tumbler, a dot, stork, or a hawk. On 28 February this year, she wore no brooch. Was she clueless on what to do?

Richard Partington, writing for the Guardian, observed that in early March she wore a funereal black. She was obviously not happy with the war and what it has in store for her and the Bank of Russia. But that did not stop Putin from giving his former economic adviser a third term which could make her the longest serving female Governor of a central bank anywhere.

Assessing Governor Nabiullina

Elvira in Russian means fair or white, or truth. With a third term due to start in June later this year, it would be too early to assess Governor Nabiullina. Notwithstanding my scepticism on such awards, it is worth mentioning that Euromoney and Banker named Governor Nabiullina as Central Bank Governor/Central Banker of the year for 2015/2017 respectively.

Valeria Gontareva headed the Ukrainian Central Bank from 2014 to 2017. The Financial Times quoted her as saying that Elvira “is a very professional, experienced macroeconomist and central banker. No doubt about that … But without values, your professionalism is nothing.”

Conclusion

Writing in 2018, Johnson concluded, “The Putin government’s alienation from Western Europe and North America, its heightened determination to pursue a more financial nationalist path, and the resulting uncertainties have increasingly put the Bank of Russia in a position where its liberal, internationalist inclinations and its national responsibilities clash.” That stands true even today.

Elvira is also the first name of one of Russia’s great athletes, a three-time Olympic gold medallist in synchronised swimming. But, the present challenge calls for a more skilled balancing act, of a different kind. The forex reserves of around USD 640 billion might prove short if matters go out of hand. Nor will a known prowess in French poetry help.

On 18 March 2022, the outlook did not look as sombre and gloomy as three weeks earlier. But, Governor Nabiullina seemed to be keeping her cards close to her chest. She wore grey, and no brooch.

Select References:

Johnson, J. The Bank of Russia: from central planning to inflation targeting, in Conti-Brown and Lastra, ed., Research Handbook on Central Banking, Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, UK, 2018.

Grossman, G. Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, in Beckhart, B.H. ed., Banking Systems, Indian Edition, Times of India Press, Bombay, 1967. With an addendum by S.R.K. Rao of Reserve Bank of India. (My undergraduate textbook)

De Kock, M.H. Central Banking. (This was also an undergraduate textbook)

© G Sreekumar 2022

For periodical updates on all my blog posts, subscribe for free at the link below:

https://gsreekumar.substack.com/

![]()