The importance of teaching ethics in management and accounting in the context of persisting cases of corporate misdemeanour and falling accounting standards.

In 2001, at an Enron press briefing announcing their financials, Richard Grubman, a Wall Street analyst, asked Jeffrey Skilling, the CEO, why Enron had not come out with a balance sheet. Bethany McLean and Peter Elkind described the exchange between them as follows:

“Skilling: “We do not have the balance sheet completed. We will have that done shortly when we file the Q. But until we put all of that together, we just cannot give you that.”

McLean and Elkind, The Smartest Guys in the Room, Page 410.

Grubman: “I’m trying to understand why that would appear to be an unreasonable request, in light of your comments about daily control of all your credits?”

Skilling: “I’m not saying we can’t tell you what the balances are. We clearly have all of those positions on a daily basis, but at this point, we will wait to disclose those until all . . . the right accounting is put together.”

Grubman: “You’re the only financial institution that cannot produce a balance sheet or cash-flow statement with their earnings.”

Skilling: “Well, you’re—you—well, uh, thank you very much. We appreciate it.”

Grubman: “Appreciate it?”

Skilling: “Asshole.”

Eight months later, the energy giant filed for bankruptcy, then the biggest corporate failure in the US. The company went down in rating from investment grade to default in four days.

Jeffrey Skilling

Jeffrey Skilling did his MBA from Harvard Business School (HBS), where he was a Baker Scholar, before joining McKinsey. In the Enron trials, Judge Lake asked him whether it was at Harvard that he learned to do all the fraud that he had done (something to that effect – I am citing from memory). Enron and other similar cases of accounting fraud and corporate misgovernance have been a source of embarrassment to top business schools whose former students were key dramatis personae in many instances.

HBS wall of shame

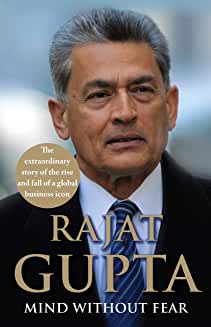

That was a time of many great cases of corporate misdemeanour. It did not help the aura of business schools that Rajat Gupta, another HBS product and Baker scholar who joined McKinsey, the same distinction and route as Skilling, and the first non-Westerner to head McKinsey, was caught in an insider trading scandal. He was then on the Board of Goldman Sachs.

But Skilling and Gupta were not the only two from the HBS wall of shame. There was Samir Barai (class of 1999), the hedge fund manager, Gregory Rorke (1980) who apart from defrauding investors also taught at the Columbia Business School, and Steve Bannon who was on the board of Cambridge Analytica, the scandal-embroiled political consulting firm, before moving to the Trump administration as chief strategist.

Add to this President Bush Jr., Hank Paulson, the Treasury Secretary, John Thain and Stanley O’Neal of Merryl Lynch, and Jamie Dimon of JP Morgan Chase, all HBS alumni, to name a few. They might not be directly involved in misdoings. But their failure to anticipate and prevent the biggest financial crisis since the Great Depression lays bare the hollowness of the HBS aura. As a report on a BBC investigation (see here) pointed out, “The world’s top business schools provided the philosophical foundation for the people who made the biggest blunders, and failed to notice the spiralling toxic debts and misplaced incentives in the finance industry.”

Why MBA?

Fraudsters come from different academic streams. So, it might be rightly asked, why focus only on MBA? That is because MBA programmes, especially the Ivy League Schools, nurture future business leaders. And, therefore, they are expected to lay the highest standards, not for themselves and for business schools across the world, but for all businesses that look up to HBS and other business schools for their publications and case studies to throw light and learn from.

One argument is that if you look at frauds across the world, the share of MBAs would be much smaller than those from other disciplines. Apart from the incongruity of thus clubbing all other disciplines together, what is material is the share of fraudsters coming out of business schools, which I bet would be much higher, as compared to those from other colleges or disciplines. This is all the more glaring when one expects these institutions to be the torchbearer of ethical standards.

Fraud in testing

Are MBAs more fraud-prone than students from other disciplines? My gut instinct, as I will explain, is that proneness is inherent in the system. In the early 1980s, there was the story of a candidate from Chennai scoring 800/800 on his GMAT. And how Robert McNamara the previous record holder called to congratulate. Later, the story goes, a few others with unusually high scores from the same centre came to light. The more imaginative version speculated that as time constraint was a critical factor, the candidates split up the questions to signalling the answers to others. In any case, several candidates from the same centre scoring high was a statistical improbability. This apparently led to the testing authorities introducing random seating. Not much is known as to what happened later to these bright kids.

I cannot vouch for the above story’s veracity. But, the fact remains that coaches and training schools teach candidates to beat the system. Such schools existed in the UK to get their wards into the Indian Civil Service even in the later 19th century (Winston Churchill had a name for them, which I forget. I will add that later). This results in gaming the entire system. As discussed below, a racket which was exposed a few years back confirms this.

Coursework malpractices

After the admission, the course work consists of a large number of tests, quizzes, group activities, and case study presentations. These involve tight deadlines and having to plod through voluminous material and difficult exercises. Do the shortcuts learnt here and the compromises made with academic integrity spill over to the working career? These questions probably require more research than what I am aware of.

Recruitment fraud

Are there malpractices in getting some of the corporates to visit certain business schools? This may not be the case with top-tier institutions. But anecdotal evidence suggests that some second-tier institutions are not above giving, and many corporate HR departments are not averse to receiving, expensive gifts in lieu of taking part in the annual placement jamborees which go by the name of campus recruitment.

Private sector institutions might have evolved their own practices of campus recruitment over the years. The Tatas, I believe, used to offer IAS probationers direct appointments to the Tata Administrative Service. Now they recruit from premier management institutes. This is what most leading private sector companies do. But, how and when did public sector undertakings enter the fray?

Campus recruitment in PSUs

My guess is that PSUs started campus recruitment at least in the mid-1980s. I am basing it on personal experience.

My STC interview

In 1985, I appeared for a selection test for the State Trading Corporation. I wrote the test in Kochi. This was followed by grilling rounds of interviews and group discussions in Chennai and New Delhi. I think it was in Delhi, going up the lift to the interview room, an employee introduced himself, and quietly advised me, don’t join this organisation! The reasons he cited are immaterial. In any case, I did not need any prodding. By then, I had an appointment letter from the Reserve Bank of India. I chose to attend the interview as it gave me a chance to visit old friends in the city. And as a backup just in case the Bank had second thoughts. They almost had!

In Delhi, I was informed that around 1,80,000 wrote the test, 180 were selected for the first interview and group discussion, and 30 were shortlisted for the final interview. I was one of the ten selected. But, I wrote a polite letter expressing my inability to join. Did STC find the entire exercise of tests across the country, first-level interviews in many cities, and final interviews in Delhi, just to select ten candidates, cumbersome? They must have. A few others like me might also have opted out. The next year, I believe, they opted for campus recruitment. But, couldn’t they have combined with other PSUs and gone for joint selection much like different civil services under the UPSC?

Campus recruitment

Campus recruitment at the Reserve Bank of India started probably in 2002 or 2003. Soon thereafter, attending a Management Development Programme in early 2003, the management consultant and corporate mentor engaged by the Bank for the purpose addressed us, participants. I will not reveal his name for two reasons. In fact, three. First, I don’t remember his name, frankly. Second, as I came to know later, he was the son of someone I had met in my childhood, an erudite and prolific literary figure in Malayalam. Third, if another one is required, his grandfather wrote a four-volume manual on Travancore in 1940 which I still refer to often though not as much as a still earlier three-volume one of 1906.

He spoke on campus recruitment and its merits during the course of his talk. I had two questions at the end. First, is it proper for a government organization like the Reserve Bank of India to select its officers only from a few educational institutes? His answer was short: not proper. My second question was how valid was the supposition that the best candidates suitable for employment at the Reserve Bank of India can be found only in a few select institutes? The short response again: not valid. I admired him for his honesty.

Supreme Court steps in

Campus recruitment continued for a long in many PSUs including RBI and public sector banks, till I think Madras High Court struck it down in 2014. They held that campus interviews violated the fundamental rights guaranteed under Article 14 (Equality before Law) and Article 16 (Equality of opportunities in matters of public employment) of the Constitution. It further held that it was unfair to citizens who were no longer pursuing formal education in any college or institution, much less the specified ones where the recruitment process was being conducted. It must have come as a reprieve for the thousands of prospective candidates who chose to study through distance education and did not get a chance to study in elite colleges. Nevertheless, going by this news report, the practice of campus recruitment by PSUs was stopped only in 2017.

MBA and campus recruitment

Why digress into campus recruitment while discussing ethics in MBA education? Because, invariably, it involved targeting MBA students to the exclusion of other streams. Is this justified? I have overheard, as a teenager, a Birla executive reason why their group preferred chartered accountants to MBAs. They felt that MBAs came with the preconceived idea that they had an answer to every problem. Much like if you have a hammer, everything looks like a nail.

But, my objections were different when the issue of campus recruitment came up for Board level discussions. I feel that having executives from just one stream, whether MBA or engineering or chartered accountancy, is flawed. I have always been a votary of sourcing employees from different streams. The strength of the Indian Civil Service, going by the account of Philip Woodruff (The Men Who Ruled India Vols 1 and 2, later republished as one volume under his real name, Philip Mason), is the different backgrounds and different kinds of thinking that came with sourcing candidates from a mix of academic backgrounds. I believe this is the case with the most successful organizations.

Even though campus recruitment has been formally dropped, some PSU banks fund the management education of students at select institutes with the understanding that they will join them. Is this campus recruitment through the backdoor? As of now, I am not sure.

Ethics in accounting

The Big Four

The period from the 1980s has not just been a period of large corporate failures where business schools alone were put in the dock. It was also a period when the Big Four in accounting, Deloitte, E&Y, KPMG, and PwC, had a lot to answer for.

Deloitte

Deloitte is short for Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu. Established in 1845, it merged with Haskins & Sells in 1972 to become Deloitte Haskins & Sells. Later, in 1989, with Touche Ross, and again in 1993 with Tohmatsu becoming Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu. About 20 years back, it merged five Indian accounting firms with it to reach its present size. These were SB Billimoria & Co., CC Chokshi & Co., PC Hansotia & Co., Fraser & Ross, and AF Ferguson & Co.

The other three

E&Y was the result of the merger of Ernst & Whinney, and Arthur Young & Co., in 1989. PricewaterhouseCoopers was also the result of a merger in 1998 of Price Waterhouse and Coopers & Lybrand. KPMG also had a similar history of mergers. The four letters come from the surnames of founders of different firms. It wanted to open an office in India. But, the Institute of Chartered Accountants of India would not allow foreign firm names. Apparently, four chartered accountants, Kapadia, Perrera, Makhijani and Girish, lent their names to start KPMG in India!

The Big Eight

Not many would recall now that in the 1980s there was a Big Eight in accounting. Among the names missing now is Arthur Andersen. It stopped its accounting arm after the collapse of Enron and allegations of conflict of interest with its consulting arm. The latter became Andersen Consultants and now Accenture. The other names which disappeared through mergers were Arthur Young, Touche Ross, and Coopers & Lybrand.

Are accounting mergers good?

Why go through this saga of mergers? It is to speculate whether these complicated mergers cutting across jurisdictions has been good for maintaining accounting standards. I will leave that as an open question.

An old story

A chartered accountant narrated a story from his article days with a “blue chip” firm now with a Big Four. One CEO received reimbursement from his company for dry cleaning 18 silk sarees at a five-star hotel where he stayed. He travelled alone. The entire lot was billed to the company. He informed the matter to the Partner, but the matter did not find a place in the audit report. Did the CEO offer to pay back the amount? I doubt. Such findings apparently do not alter the way companies are run; they perhaps just change the terms of negotiation between the auditor and the audited. They also illustrate how social niceties take precedence over public responsibilities. Can any type of education overcome this? Either you have it or you don’t.

Teaching ethics in business and accounting

Ethics in management

Many unsavoury incidents from around the 1980s till the first decade of this century led to evolving MBA Oath in 2010. It describes itself as “a voluntary pledge by MBAs to create value responsibly and ethically, administered by a volunteer team of MBA graduates.” It is also available as a book, “The MBA Oath: Setting a Higher Standard for Business Leaders” (see here). See here to know about and take the oath.

Around this time, Srikant Datar of HBS, along with two colleagues, David Garvin and Patrick Cullen, worked towards revamping MBA Education. In their “Rethinking the MBA – Business Education at a Crossroads” (Harvard Business Press, 2010), they underlined, among other things, the need to focus on accountability, ethics, and social responsibility. Specifically, they suggested action learning as a solution for creating ethical sensitivity. Summarising the views of deans and corporate executives (as most of the book is), they wrote that “…critical leadership capabilities such as exercising influence, creating engagement, driving towards completion, and behaving ethically in stressful, competitive situations, are best learned by doing. That requires immersion in challenging, real-world projects.” HBS itself started a full-length course on ethics in 2004.

The New York University’s Stern School of Business had been offering a Professional Responsibility course since 1994. It used to focus on the regulatory and legal requirements of the business but now explores their role in society, too. Many others followed suit. We will see below where they stand.

Ethics in accounting

The Association of Chartered Certified Accountants (ACCA), the global professional accounting body, has included an Ethics and Professional Skills Module. See its page on ethics here. Its fundamental principles now include integrity: “Members should be straightforward and honest in all professional and business relationships. The ACCA’s Rulebook, and the Code of Ethics of the International Federation of Accountants (IFAC) state that “integrity implies not merely honesty, but fair dealing and truthfulness.” The ACCA also emphasises “digital ethics,” which includes data privacy. There are, however, questions on what is material in financial and non-financial data that need to be shared, which are not yet satisfactorily addressed.

Recent frauds

Has there been improvement? Is there hope? Seb Murray in two articles in Financial Times (13 June 2022) on its Business Education page (page 6), titled ‘Course leaders want more time to fight crime,’ and ‘Teaching virtues and values to accountants,’ cite the challenges facing management education and training of accountants. These articles are the motivations for writing this post.

Notwithstanding the above initiatives, stories of corporate misdemeanour and accounting lapses continue unabated. One of the Big Four signed off the accounts of some of the recent frauds in Wirecard, Carillion, and Petrobras. I posted earlier on Wirecard and an update is due.

In Enron, the scandal involved the staid old method of accountants making money on the side through dubious but lucrative consulting assignments. The good news is that such unethical proclivities have not been untouched by innovation and the search for greener pastures. A recent scandal implicating internal accountants related to certifying spurious environmental credentials. This incident in the German DWS Group, which also implicates Deutsche Bank, has been dubbed greenwashing. It is an innovation in fraud and means the fraudulent promotion of an eco-friendly and environmentally aware image.

In 2019, three HBS and two Stanford alumni were among 33 caught in the biggest admission racket in the US. One was willing to pay one million dollars to ensure that both his daughters got admission to Harvard and Stanford. The investigation was code-named Operation Varsity Blues. It revealed impersonation, falsified scores, extra time on tests, and changing answers. Among other devious methods, they also faked sports profiles and bribed coaches and other insiders. See here and here.

The issues

According to Murray, “These scandals have intensified concerns that a poorly developed approach to teaching behavioural, as opposed to technical, skills is reducing ethical standards and professional independence. Failings have included auditors not testing assumptions or the accuracy and completeness of management reports. Company directors have also been accused of prioritising their own financial rewards over transparency.”

The Edhec Business School in France hired a philosopher to take its finance students through the grey area of morality and criminal behaviour. The progress has however not been smooth elsewhere. As Murray points out, “financial crime is still regarded as a backwater of global finance studies, not a central focus of the curriculum. Many students are uninterested in a career fighting white-collar criminals and kleptocrats, and there are limited job opportunities for all but those with a very specific skill set and experience.”

He sums up the issue thus: “Business schools still face manifold challenges in delivering the competencies that students need to fight financial crime, however. A need for legal knowledge means that many universities deliver programmes on economic crime through their law departments rather than business schools.”

Murray quotes Helen Brand, Chief Executive of ACCA, as saying that “Rather than being able to recite the code of ethics and conduct, everyone must be able to apply the theory.” But, in developing this ability, academicians cite the limited space available for accommodating both “soft” behavioural skills and “hard” technical abilities. Whatever be the resultant tension, Brand warns against diluting the ethical component to accommodate more technical inputs.

The way forward

Students learn ethics not just from textbooks but also from how their universities and their departments are run. They also pick up values at business schools outside of the curriculum. When they look around, they can see that if you are related to a donor, the chances of selection go up to 42%. And how those joining on sports recommendations play no sport. They cannot be kept inured from its effects.

Business schools and professional bodies perhaps still do not consider it their responsibility to increase input on ethical education. Their initiatives seem limited to adding an elective and saying the right things in the ethics code. They might consider it the primary responsibility of family, society, religion, and personal values, something like language and manners, that one needs to pick up on one’s own down the road.

In my view, stand-alone ethics courses are not likely to succeed unless they are made mandatory. Alternatively, inputs on ethics should be weaved into case studies in other core courses. The emphasis should be on simulations where students are made aware through cases and exercises in their course work of corporate cultures that can lead to unethical behaviour. The duration of an MBA and accounting education could also be increased to accommodate ethical and other technical inputs. After all, it is important to prepare a more well-rounded product than a half-baked one for the huge pay-check that is waiting.

It will also help if universities themselves, their business schools, their admission processes, their academic and administrative processes, and placement initiatives, are also run ethically.

Postscript

By the way, Skilling and Gupta, like many others in the US and elsewhere, were convicted long back. They are now free birds, having served time, ready to hit the lecture circuit and book-signing sessions. Gupta already has one book under his belt, Mind Without Fear. Even Skilling might come out with one: Skilling on Skilling? As the honourable Supreme Court of India observed recently while commuting a death sentence, even a rape-murder convict can become a socially useful individual after release from jail.

Two of the biggest cases of corporate fraud in India, Global Trust Bank and Satyam Computers, both based in Hyderabad, had the same non-executive director, an HBS don, and the same auditor, one of the Big Four. They are still in business. The auditing firm even helped my Bank draft a code of ethics. I attended one of their sessions in 2013, also in Hyderabad.

Taking a cue from the Honourable Court’s observation, in restorative justice, there can be life after a sentence. But what seems missing is the sentence itself. The HBS don’s Wikipedia page states that one of the cases, going back almost a decade and a half, is under appeal. As if that amounts to acquittal.

This reminder is for those who are pursuing equally old or older cases in India, awaiting prosecution and conviction, forget about the release. Not to forget about fretting and agonising on the sorry state of the Ganges. Just saying.

© G Sreekumar 2022

For periodical updates on all my blog posts, subscribe for free at the link below:

https://gsreekumar.substack.com/

![]()